Being turkey season, the internet is seriously abuzz at this time of year with folks who are investigating the notion of brining their holiday bird. It seems people are on a seemingly never-ending quest for a better bird. The common refrain from people I talk to is, "So, what's the deal with this brining thing? Does it really make that big of a difference?"

In this post I hope to help explain why brining really is a very good thing indeed.

Let's face it, most of us probably grew up eating holiday turkey that was dry and generally lacking in the flavor department. I think this is why my grandfather always shunned the balsa-wood-like white meat for the far more moist and flavorful dark stuff. To this day I am firmly in the dark meat camp, but I digress.

Brining is all about pure science, but it's certainly not rocket surgery. Let's break it down and, as a favorite preacher of mine often said, put the cookies on the shelf where the kiddies can get to them.

The entire process of brining can be described by the scientific axiom that nature abhors a vacuum. When you submerge meat in a solution of water, salt and sugar, you have created a vacuum that nature simply must remedy. See, nature likes to have things in a nice balance called equilibrium. She doesn't like you gumming up the works. You've created an imbalance where the concentration of the water, salt and sugar outside the meat is much higher than that inside the meat.

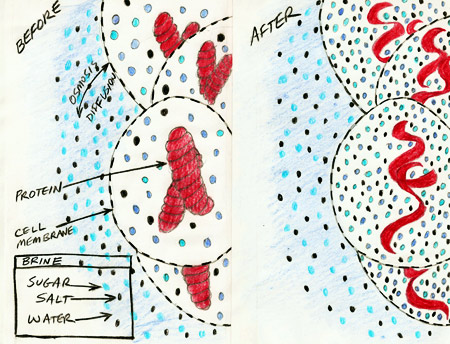

Given this situation, nature goes to work trying to reestablish its required equilibrium. The cells inside the meat are surrounded by a semi-permeable membrane. Small molecules like water, salt, and sugar can pass through this membrane, but larger molecules like proteins cannot.

Through a process of osmosis by diffusion, the cell moves water, salt and sugar in and out of the cells trying to get things back into balance with the surrounding liquid. Also, since most brines contain flavorings in the solution, the cell unwittingly seasons itself as it allows the brine into the cells.

But wait, there's more.

As the salt concentration in the cell increases it causes some of the tightly-wound proteins to unravel, or denature, and relax a bit. This allows the cell to take on even more of the solution. Some proteins in the cell actually denature completely and are liquefied.

Here's a crude illustration that I've drawn to show what I've described.

The magic of brining continues during cooking. When the meat is heated, the proteins bind with one another and squeeze out moisture. However, brining adds 10% or more moisture weight to the meat. So, even though the cooking will cause a 20% weight loss in moisture, we started 10% or more ahead of the game, so the actual moisture loss is cut in half, resulting in more moist meat.

Also, remember those proteins that were completely denatured? Well, those proteins are no longer available to do the protein-binding mambo, so the meat is more tender.

I hope this gives you a better understanding of how brining works, and why it's a wonderful way to let nature help you cook a much better bird.

Tips:

- Brining is also great for other meats that can use a little help, like pork.

- When brining an "enhanced" bird (injected with a solution), cut the amount of salt in the brine by half.

- A good time guideline for brining is 45 minutes per pound.

- Always rinse brined meats well before cooking.

- You don't need to cook to 180º. The FDA guideline is now 165º.

My brine recipes:

Turkey recipes:

Post a Comment

Note: Comments containing profanity or blatant promotion/spam will not be published